A Short Overview of Slovene Literature from Romanticism to Modernism

18th century's libertarian spirit

The 17th and 18th centuries were dominated by folk and religious poetry, but also saw the beginnings of Slovene drama. The poems of Valentin Vodnik (1758–1819) and the plays of Anton Tomaž Linhart (1756–1795) expressed the libertarian spirit of the French Enlightenment and the French Revolution. The formal simplicity of their work, which is close to popular rhymes in theme and expression, is no accident: they were aware that they were writing for the first literary public of their nation. This new public literary consciousness was made possible by the educational reforms of Austrian empress Maria Theresa, and the ensuing mass literacy of the region's populations.

Romanticism and Prešeren

The next important stage in Slovene literature came as late as the beginning of the 19th century, with the advent of Romanticism. The German Romantics influenced both the content and form of Slovene poetry, while the wider European Romantic movement and its accompanying nationalism inspired Slovene intellectuals to produce philological and literary works. Jernej Kopitar (1780–1844) initiated early attempts to standardise and codify the Slovene language. In the 1830s and 1840s Matija Čop (1797–1835) was active in publishing literary works and literary periodicals in Slovenia.

France Prešeren

The key personality of this belated Slovene 'renaissance' was Dr France Prešeren (1800–1849), a lawyer and free thinker, a bohemian and an eternally indomitable spirit. After a period of study in Vienna as a student of law, Prešeren developed considerable mastery of classical poetic forms, primarily ballad and sonnet forms in such works as Povodni mož ('The River Man'), Slovo od mladosti ('A Farewell to My Youth'), Ljubezenski soneti ('Love Sonnets'), Nova pisarija ('The New Writing') and the romance Hčere svet ('The Daughter's Advice').

In 1833 he began an unrequited love affair with Julija Primic, the daughter of a rich Ljubljana merchant, to whom he dedicated his Sonetni venec ('A Wreath of Sonnets') of 1834. Dogged by controversy like his hero Byron, and often falling foul of the censor, he continued to produce remarkable poetry in Slovene until the end of his life, when he faced the ruin of his unsuccessful legal practice in Kranj. He died ill and mired in debt in 1849.

Prešeren's legacy

Prešeren spiritually rekindled the sub-Alpine province with the fighting spirit of the European Romantics and thus articulated the national consciousness. Although he was not a prolific writer, his work gave new life to Slovene literature. The themes and prosodic structure of his verse set new standards for Slovene writers, and his lyric poems are among the most sensitive, original and eloquent works in Slovene.

In 1844 he composed Zdravljica ('A Toast'), which was adopted in 1994 as the Slovenian National Anthem. Each year since 1947, on the 8 February national cultural holiday which commemorates the anniversary of the death of the poet, Prešeren Award and Prešeren Foundation Awards, the highest national awards in the field of arts, are bestowed. On 3 December, the date of his birth, many cultural institutions in Slovenia open their doors to visitors late into the evening, offering free presentations, performances, exhibitions, screenings and other cultural events.

Prešeren’s national epic poem Krst pri Savici ('The Baptism by the Savica', 1836) discusses the conflict between paganism and the early Slovene converts to Christianity and illustrates Prešeren's patriotism, pessimism and resignation.

Later this theme of war was also taken up by dramatist Dominik Smole (1929–1992), while in recent years a postmodern interpretation of Krst pri Savici entitled Krst pod Triglavom ('Baptism Below Triglav') has been staged at Cankarjev dom, Cultural and Congress Centre in Ljubljana in the form of a multimedia spectacle directed by Dragan Živadinov in accordance with the concept of Neue Slowenische Kunst.

19th and early 20th centuries

The 19th century, the golden age of novels, provided the first Slovene example of this new literary form with The Tenth Brother by Josip Jurčič (1844–1881). The model for this and for Jurčič's other tales was the English historical novel, adapted to the environment in which they were created: they were set in the time of Turkish raids, and dealt with imagined erotic passions in a province where the sharp division between estate owners and villagers forbade close links.

Jurčič was also the first Slovene journalist who, together with Fran Levstik (1831–1887), created the basis of Slovene literary criticism. Janko Kersnik (1852–1897) and Ivan Tavčar (1851–1923) also created high-quality short stories and chronicles on Slovene rural life. Janez Trdina (1630–1905), long known only as a collector of popular pieces, was in reality a discerning observer and honest recorder of life in these parts. He finally obtained his rightful recognition after the publication of his diaries in the 1980s.

The age of Realism, which was marked by great novels from Slovenia, also found expression in poetry, including the works of Impressionists such as Josip Murn Aleksandrov (1879–1901), the Symbolist Oton Župančič (1878–1949) and later Expressionist Alojz Gradnik (1882–1962).

Moderna

The generation of the so-called Moderna, which appeared at the turn of the 20th century, was dubbed 'the damned poets movement', having its origins in European symbolism and decadence. Josip Murn Aleksandrov was a poet attached to the popular poetic tradition, which he reworked into sensitive modern poetic miniatures. During his short life, Dragotin Kette (1876–1899) wrote with more cheerfulness and energy than any previous Slovene poet.

The undisputed cultural and spiritual authorities of this period were Ivan Cankar (1876–1918) and Oton Župančič, who even exerted an influence on political life. Cankar wrote the stories Hlapec Jernej in njegova pravica ('Bailiff Yerney and His Rights', 1907), Hiša Marije pomočnice ('The Ward of Our Lady of Mercy', 1904) and Podobe iz sanj (‘Images from Dreams’, 1920) and the novels Martin Kačur (1906) and Novo življenje (‘New Life’, 1908), as well as Ibsenesque plays like Kralj na Betajnovi (‘The King of Betajnova’, 1902) about the disintegration of provincial values at a time of growing industrialisation and the advance of capital. Cankar was also an enthusiastic essayist and propagated the idea of a Yugoslav state.

Oton Župančič, whose explicitly modern approach to poetry and powerful personality made him the standard for other poets for years to come, also supported the national resistance.

Recently the work by Zofka Kveder (1878–1926), one of the first Slovene women writers and feminists is gaining more attention and research.

Between the wars

After World War I, social and spiritual tension was evident in the predominantly Expressionist poetry of Tone Seliškar (1900–1969), Lili Novy (1995–1958) and Anton Vodnik (1901–1965), as well as in the plays of Slavko Grum (1901–1949).

Between the wars, the novel and short story revival was dominated by Social Realism; particularly outstanding during this period were the works of Lovro Kuhar-Prežihov Voranc (1893–1950), Miško Kranjec (1908–1983) and Ciril Kosmač (1910–1980). Ciril Kosmač reached his peak only after the war, with a shift to a more contemporary mode of narration; his Tantadruj blurs the boundary between reality and fiction.

In the 1930s Vladimir Bartol (1903–1967), psychologist by training and Nietzchean by conviction, wrote the eccentric novel Alamut, the story of an Islamic empire whose Emperor retained power by skilfully manipulating his servants' pleasures. Alamut was translated into Czech (1946), Serbian (1954), French (1988), Spanish (1989), Italian (1989), German (1992 - from French!), Turkish, Persian (1995), Arabic, Greek, Korean, Hebrew, Hungarian and other languages. An English translation appeared in 2004 by Scala House Press in Seattle, USA. Alamut was presented on stage for the first time ever in July 2005 at the Salzburg Summer Festival. Directed by Sebastijan Horvat (EPI Centre), the production was the result of collaboration between the Salzburg Festival and the Slovene National Theatre Drama Ljubljana. The script was written by Dušan Jovanović.

Mighty Modernism

Edvard Kocbek (1904–1981), Jože Udovič (1912–1986) and Ivan Minatti (1924–2012) developed highly-articulated lyrics within the cultural expression of the Slovene national resistance during World War II and continued their writing into the post-war era, while Karel Destovnik-Kajuh (1922–1944) and France Balantič (1921–1943) lost their lives on different sides, at the start of their promising careers. Kocbek later became an important dissident and an influential symbol as well as a fruitful poet and essayist.

A new generation appeared with ‘The Poems of Four’, which introduced Kajetan Kovič (1931–2014), Janez Menart (1929–2004), Tone Pavček (1928–2011) and Ciril Zlobec (1925–2018) who were to remain on the scene until the beginning of the 21st century, thus representing one of the most influential groups in Slovene poetry.

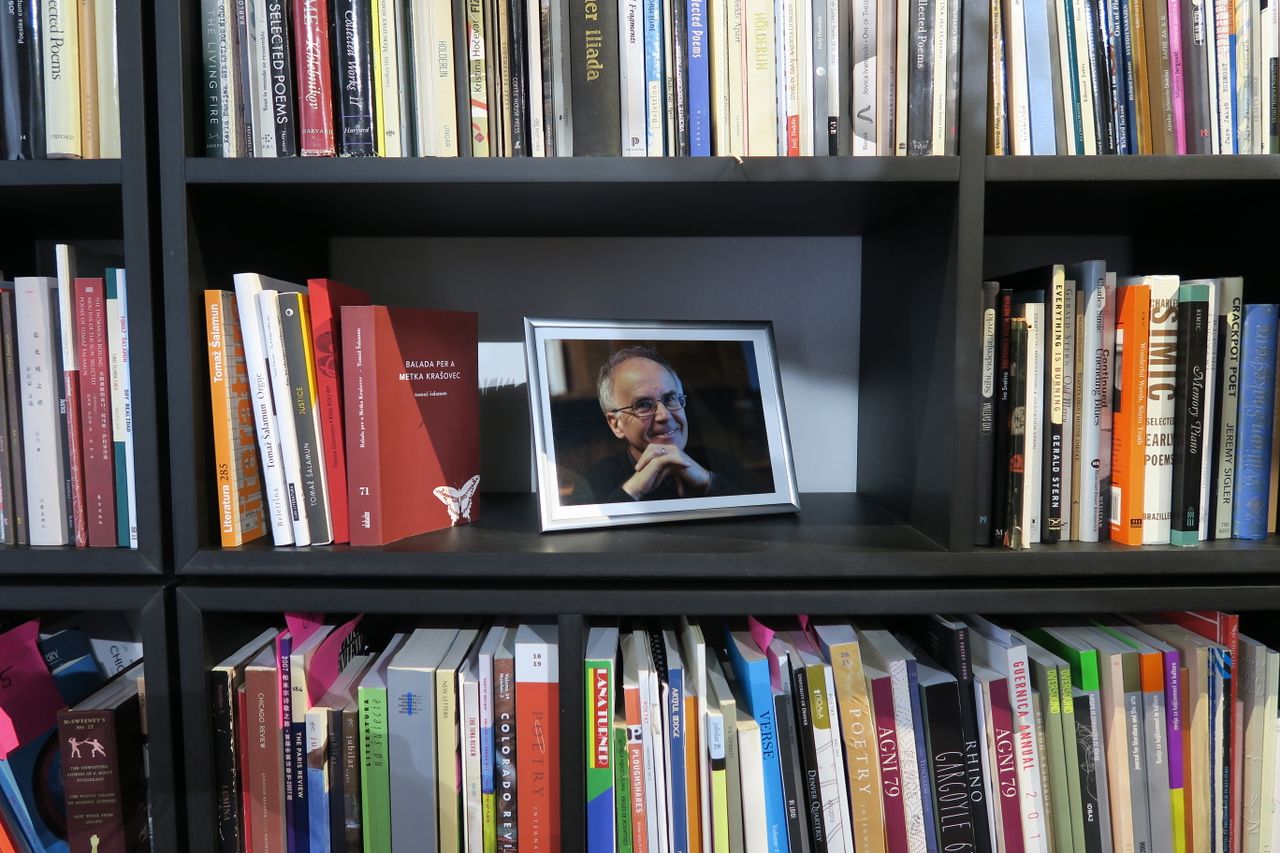

Their contemporaries Gregor Strniša (1930–1970) and Dane Zajc (1929–2005) brought a more radical and dark modernism through poetry and drama. Dominik Smole, with his version of Antigone, became the leading dramatist of his generation. The poetry collection Tercine za obtolčeno trobento ('Tercets for the Damaged Trumpet', 1985) by Veno Taufer (1933–2023) broke away from previous linguistic experiments, opting rather for an intimate and personal lyricism. Taufer was followed by younger authors such as Niko Grafenauer (b 1940), who attempted to solve his existential conflict through a formalistic and stylistic penetration into language, and Svetlana Makarovič (b 1939), whose originality sprung from pessimistic existential feelings. Tomaž Šalamun (1941–2014), a poet who aimed not to imitate reality but rather for a fluid and sophisticated word play, constantly and radically defied the traditions of the older generation.

The group of poets born around 1950, including Ivo Svetina (b 1948), Milan Dekleva (b 1946) and in particular Milan Jesih (1950), triumphed in the 1970s and remained influential throughout the 1980s. Jure Detela (1951–1992), during his short yet intense life, and Ifigenija Zagoričnik (b 1933) explored the relationship between the Self and the Other, while Boris A Novak (1953) pledged loyalty to aesthetic formalism.

Post-war prose writers, like Rudi Šeligo (1935–2004), Vladimir Kavčič (1932–2014), Andrej Hieng (1925–2000) and Lojze Kovačič (1928–2004) brought different achievements in modern storytelling, Šeligo being the most radical and closest to the French nouveau roman (Ali naj te z listjem posujem, 1971), while Kovačič seems to have left the deepest impact with his existential, rough prose ('The Newcomers', 1984–85), together with the older but ever experimenting Vitomil Zupan (1914–1987) ('Menuet for a Guitar' 1975).

First tendencies to post-modernism may be observed in Drago Jančar's (b 1948) novel Severni sij ('The Northern Light', 1984) and short stories Smrt pri Mariji Snežni ('The Death at Marija Snežna', 1985) and Pogled angela ('Angel Look', 1992).

Marko Švabić (1949–1993), Berta Bojetu (1946–1997), Branko Gradišnik (b 1951), Milan Kleč (b 1954), Emil Filipčič, Uroš Kalčič, and Boris Jukić, all born around 1950, wrote the pages of imaginative, playful, poetical and experimental prose, sometimes with elements of metafiction (Gradišnik) or magical realism (Jukić). Brina Svit (born as Brina Švigelj, 1954) started her career as a Slovene authoress (Con brio, 2002) and now, after having moved to Paris, continues writing in French (Moreno, 2003).