About Slovenia

This section looks at the long history of the country, spanning from Roman times to the third millennium, and stretching between the Alps, the Adriatic and the Pannonian Plain. It presents its land and peoples as well as its political, economic and cultural structures.

Geography and topography

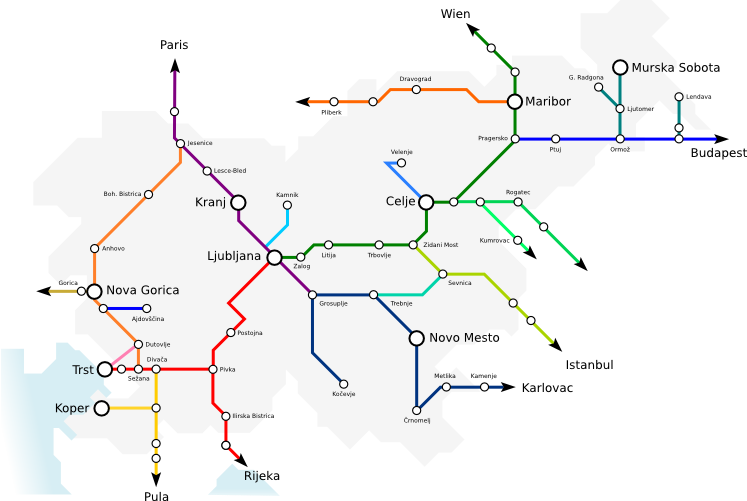

Slovenia covers an area of 20,273 square kilometres between the Alps, the Adriatic and the Pannonian Plain. With Austria to the north, Italy to the west, Hungary to the east and Croatia to the south, Slovenia has always been a crossroads of trans-European routes. The port of Koper is a unique Central European sea gateway; the roads and the railway (which as early as 1857 connected Vienna and Trieste) link the Danube region with the Mediterranean, whilst north west-south east connections link Central Europe with the Balkans.

The largest part of Slovenia is taken up by the Alps, with several river sources and waterfalls and numerous endemic species of flora and Alpine fauna. 47.3 per cent of the country's population lives in the pre-Alpine hills and valleys. The Alpine region stretches over much of the territory in the northern half of Slovenia, and includes Mount Triglav (2,864 metres high), a large protected natural area of 83,807 hectares, and the Ljubljana and Celje basins, which rank among the most densely-populated parts of Slovenia. Slovenia is the third most forested country in Europe, with 58 per cent of its land area covered by woods and forests. It is also here that the Adriatic reaches deepest into Central Europe and exerts its climatic influence over 8.6 per cent of the country’s territory, resulting in a vine-growing and fruit-cultivating hinterland. In the lower Mediterranean part of Slovenia, the limestone landscape phenomena - numerous karst sinkholes and swallow holes and more than 1,000 caves and chasms - gave the name to the branch of science known as 'karstology'. In the south of Slovenia there is the cool and damp Dinaric, a north-eastern section of the Dinaric Alps which covers 28.1 per cent of Slovene territory. This is the most forested part of the country with plenty of game, and consists of the Cerknica Intermittent Lake (its waters disappear in the Spring) and the Postojna karst cave of 19.5 kilometres. Finally there is the Pannonian region in the east (accounting for 21.2 per cent of territory), the most fertile farmland in Slovenia, rich with vineyards and thermal and mineral waters.

The country's geographical diversity results in several different types of climates in Slovenia: continental, Alpine and Mediterranean. Approximately 11 per cent of the Slovene countryside is protected by legislation as natural heritage, the largest area being the Triglav National Park with its surface area of 848 square kilometres. The Škocjan caves were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1986, and the Sečovlje Salt Pans and Cerknica Lake are included on the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance. Slovenia is also home to more than 3,200 plant species and 15,000 animal species, and is one of the few countries in Europe with a stable and vital brown bear population.

Regions

When speaking of the separate areas of Slovenia, regional names are more commonly used than geographical ones, however it is very hard to define the exact borders between them. Generally, Gorenjska (Upper Carniola) stretches from the centre up into the north and north west of the country, Štajerska (Styria) and Prekmurje (the Mura River region) extend towards Hungary in the east, Koroška (Carinthia) follows the Drava river in the north east, Notranjska (Inner Carniola) is located in the south west, Dolenjska (Lower Carniola) stretches from the centre towards the south, Bela Krajina (White Carniola) runs along the Croatian border in the south and Primorska (the coast and its hinterland along the Italian border) is situated in the west. Gorenjska is mainly Alpine and Primorska Mediterranean, but Štajerska reaches into the Pannonian Plain, and Notranjska into both Dinaric and Mediterranean types of landscape.

For the purposes of the Culture.si portal the devision into 8 parts is used according to the post codes. For better orientation:

- SI-1 for 1000 Ljubljana and other towns in central Slovenia region including Zasavje;

- SI-2 for 2000 Maribor and other towns in eastern Slovenia – Štajerska region (Styria), including Koroška (Carinthia) along the northern border;

- SI-3 for 3000 Celje and other towns in eastern Slovenia (Savinjska region)

- SI-4 for 4000 Kranj and other towns in northern Slovenia – Gorenjska region (Upper Carniola);

- SI-5 for 5000 Nova Gorica and other towns in north-western Slovenia (Goriška region), including Posočje region;

- SI-6 for 6000 Koper-Capodistria and other towns in south-western Slovenia – Littoral and Notranjska region (Inner Carniola);

- SI-8 for 8000 Novo mesto and other towns in southern Slovenia region – Dolenjska (Lower Carniola) including Posavje;

- SI-9 for 9000 Murska Sobota and towns in eastern Slovenia – Prekmurje region

However, the website also previews the introduction of the new districts/regions division in the future.

History

From Prehistoric Times to the Celts

Slovene territory was inhabited in prehistoric times and there is evidence of human habitation around 250,000 years ago. Perhaps the most important find is a flute discovered in Divje babe above the Idrija valley, dating from the Wurm glacial age when the area was inhabited by Neanderthals.

In the late Stone and Bronze Ages, the inhabitants of the area were engaged in livestock rearing and farming. Subsequently, during the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, the Urnfield culture existed in this region. Fortified hilltop settlements and beautifully-crafted iron objects and weapons were typical of the Hallstatt period (Most na Soči, Vače, Rifnik, St. Vid near Stična).

In the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, present-day Slovenia was occupied by Celtic tribes. They formed the first state, called Noricum. The names of many present places (Bohinj, Tuhinj) date from this time, as well as the names of rivers (the Sava, the Savinja, the Drava). Noricum was annexed by the Roman Empire around 10 BCE.

Roman rule and Slav settlement

The Romans established posts at Emona (Ljubljana), Poetovia (Ptuj) and Celeia (Celje) and constructed trade and military roads that ran across Slovene territory from Italy to Pannonia. In the 5th and 6th centuries, the area was exposed to invasions by the Huns and Germanic tribes during their incursions into Italy. After the departure of the last Germanic tribe - the Langobards - to Italy in 568 CE, the Slavs from the East began to dominate the area. After the successful resistance against the nomadic Asian Avars (from 623 to 626 CE), the Slavic people united with King Samo’s tribal confederation, whose centre was in what is now the Czech Republic. The confederation fell apart in 658 and the Slav people, located in present-day Carinthia, formed the independent duchy of Carantania, based at the Krn Castle, north of today's Klagenfurt (Austria). Until 1414 a special ceremony of princes of Carantania took place, conducted in Slovene language.

The Carantania duchy

In the mid 8th century Carantania became a vassal duchy under the rule of the Bavarians, who began spreading Christianity. Three decades later Carantanians together with the Bavarians came under Frankish rule. At the beginning of the 9th century the Franks removed the fractious Carantanian princes, replacing them with their own border dukes. Consequently, the Frankish feudal system reached the Slovene territory.

The Magyar invasion of the Pannonian Plain in the late 9th century effectively isolated the Slovene territory from the other western Slavs. Thus, the Slavs of Carantania and of Carniola to the south began developing into an independent nation of Slovenes. After the victory of Emperor Otto I over the Magyars in 955 CE, Slovene territory was divided into a number of border regions of the Holy Roman Empire. Carantania, being the most important, was elevated into the Duchy of Great Carantania in 976 CE (the 'Freising Manuscripts', a few prayers written in Slovene, date from this period). In the late Middle Ages the historic states of Štajerska (Styria), Koroška (Carinthia), Kranjska (Carniola), Gorizia, Trieste and Istria were formed from the border regions and incorporated into the medieval German state.

Habsburg rule, the counts of Celje, Turkish incursions and peasant revolts

In the 14th century most of the territory of Slovenia was taken over by the Habsburgs. The counts of Celje, a feudal family from this area who in 1436 acquired the title of state counts, were their powerful competitors for some time. This large dynasty, important at a European political level, had its seat in Slovene territory but died out in 1456. Its numerous large estates subsequently became the property of the Habsburgs, who retained control of the area right up until the beginning of the 20th century. Thereafter intensive German colonisation diminished Slovene lands, and by the 15th century they were of a similar size to the present-day Slovene ethnic territory.

At the end of the Middle Ages life was fraught with Turkish raids and the introduction of new taxes. In 1515 a peasant revolt spread across nearly the whole Slovene territory and in 1572-3 the united Slovene-Croatian peasant revolts wrought havoc throughout the wider region. Uprisings, which often met with bloody defeats, continued throughout the 17th century.

From Reformation and the first books in Slovene to the Enlightenment and first school programmes in Slovene

The Reformation, represented mainly by Lutheranism, spread across Slovene territory in the middle of the 16th century. This helped to establish the underpinnings of the Slovene literary language. In 1550 Primož Trubar published the first two books in Slovene, Katekizem and Abecednik ('Catechism' and 'Abecedary') - see Literature. The Protestants published around 50 books in Slovene, including the first Slovene grammar book and a translation of the Bible by Dalmatin in 1584. At the beginning of the 17th century Protestantism was suppressed by monarchic absolutism as well as by the Counter Reformation of the Catholic Church which introduced the new aesthetics of Baroque culture. The Enlightenment in Central Europe, particularly under the Habsburg monarchy, was a progressive period for the Slovene people. It hastened economic development and facilitated the appearance of a Slovene middle class. Under the reign of Emperor Joseph II (1765-1790) many societal infrastructures were established, including land reforms, the feudal system, the modernisation of the Church and compulsory primary education conducted in the Slovene language (1774). The start of cultural-linguistic activities by Slovene intellectuals of the time brought about a national revival and the birth of the Slovene nation in the modern sense of the word. Before the Napoleonic Wars Slovenes acquired some secular literature, along with the first historical study based on the ethnic principle by Anton Tomaž Linhart and the first comprehensive grammar by Jernej Kopitar.

19th century: From Napoleon’s Illyrian Provinces and Romantic movement to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy

When Napoleon captured the south-eastern Slovene regions (consisting of Upper Carinthia, Gorizia, Trieste, Istria, Dalmatia and Carniola and Croatia south of the river Sava), the Illyrian Provinces of the French state (1809-1813) were created and Ljubljana was made their capital. The short-lived period of French rule which followed changed the taxation system and improved the position of the Slovene language in schools; it did not, however, abolish feudalism. It was at this juncture that France Prešeren, a poet representative of Slovene Romanticism, asserted the right to a unified written language for all Slovenes, defending it against attempts to blend it into the artificial Illyrian language of the Southern Slavs. The first Slovene political programme, called Unified Slovenia, emerged during the European Spring of Nations in 1848. It demanded that all the lands inhabited by Slovenes should be united into Slovenia, an autonomous province with its own provincial assembly within the framework of the Habsburg monarchy, where Slovene would be the official language. In 1867 Slovene representatives received a majority of votes in the provincial elections. In the same year, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was established and split into two equal parts. Most of the territory of present-day Slovenia remained in the Austrian part of the monarchy, while Pomurje fell into the Hungarian part. The Slovenes in Veneto had already decided in 1866 to join Italy. The idea of a unified Slovenia remained the central theme of the national-political efforts of the Slovene nation within the Habsburg monarchy for the next 60 years. By the end of the 19th century industry had developed considerably in Slovenia and the population had become as socially differentiated as in other European nations.

World War I, the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The First World War brought heavy casualties to Slovenia, particularly on the bloody Soča front in Slovenia's western border area. In 1917, as the imperialistic policies of the superpowers threatened to split Slovene territory among a number of states, Slovene, Croatian and Serbian representatives brought before the Vienna Parliament the May Declaration, which advocated the creation of a unified state of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs living within Habsburg territory. This declaration was rejected, but following the dissolution of Austro-Hungarian Empire in the aftermath of the war, a National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs took power in Zagreb on 6 October 1918. On 29 October independence was declared by the Croatian parliament and by a national gathering in Ljubljana, declaring the establishment of the new state of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. Despite disagreements, and against a background of pressure from the Serbs for unification and moves by the Italians to take more territory than had been agreed, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was proclaimed on 1 December 1918 in Belgrade by Alexander Karađorđević, Prince-Regent for his father, Peter I of Serbia. Eight years later the new state became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia under the personal dictatorship of the king. Following a plebiscite in 1920, the Slovene part of Carinthia was annexed to Austria. Thereafter the Slovene nation within the centralised Yugoslavia had less and less constitutional and legal autonomy, but preserved its ethnic compactness and managed to develop both economically and culturally.

World War II and the post-war Republic of Yugoslavia

In April 1941, during the Second World War, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was attacked by Germans and Slovene territory was divided between Germany, Italy and Hungary. In the same year the Liberation Front of the Slovene Nation was founded in Ljubljana and began armed resistance against the occupying forces. Within the Liberation Front the Communist Party soon adopted the leading role. At the end of the war the partisan army liberated most of ethnic Slovenia. In October 1943 an assembly of representatives of liberation movement decided that Slovenia would join the new Yugoslavia. In 1945 the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY) was declared, uniting Slovenes, Croatians, Serbs, Bosnians, Macedonians and the other nations living in Montenegro, Vojvodina, Kosovo and Metohija. By 1947 all private property had been nationalised. After the break with the Soviet Union in 1948, Yugoslavia began introducing a milder version of authoritarian system, based on common ownership and self-management. In 1956 Josip Broz Tito, together with other leaders (Nehru of India, Sukarno of Indonesia, Nasser of Egypt and Nkrumah of Ghana), founded the Non-Aligned Movement.

The road to independence

Slovenia’s economy developed rapidly, particularly in the 1950s when the country was strongly industrialised. Despite restrictive economic and social legislation within Yugoslavia, Slovenia managed to preserve a high level of economic development with a skilled workforce, working discipline and organisation. After the economic reform and further economic decentralisation of Yugoslavia in 1965 and 1966 Slovenia was approaching a market economy. Its domestic product was 2.5 times the average, a fact which strengthened national confidence among the Slovenes. After the death of Tito in 1980 the economic and political situation in Yugoslavia became very strained, leading ultimately to the dissolution of the state 10 years later.

The first clear demand for Slovene independence was made in 1987 by a group of intellectuals in the 57th edition of the magazine Nova revija, and demands for democratisation in the centralised Yugoslavia were sparked off. In April 1990 the first democratic elections in Slovenia took place and the united opposition movement DEMOS led by Jože Pučnik emerged victorious. In the same year more than 88 per cent of the electorate voted for a sovereign and independent Slovenia. This was followed on 25 June 1991 by a declaration of independence. The very next day, the newly-formed state was attacked by the Yugoslav Army. After a 10-day war a truce was called and in October 1991 the last soldiers of the Yugoslav Army left Slovenia. In November a law on de-nationalisation was adopted, followed in December by a new constitution.

The European Union recognised Slovenia in January 1992, and the UN accepted it as a member in May 1992. Slovenia joined the European Union and NATO on 1 May 2004. Slovenia has one Commissioner in the European Commission, and seven Slovene parliamentarians were elected to the European Parliament at elections on 13 June 2004. In 2004 Slovenia also joined NATO. Slovenia subsequently succeeded in meeting the Maastricht criteria and joined the Eurozone (the first transition country to do so) on 1 January 2007.

Government

1991: Parliamentary democracy

The Constitution of the Republic of Slovenia, which was adopted by the National Assembly on 23 December 1991, laid the foundations for the parliamentary democracy, the legal system (which is based on respect of human rights and fundamental freedom), the principle of a legal and socially-just state, and the separation of legislative, executive and judicial powers. The Constitution can be amended following a proposal made by 20 National Assembly deputies, by the Government, or by at least 30,000 voters.

Head of State

The President of the Republic is elected for a maximum of two five-year terms by direct elections. The President represents the Republic of Slovenia and is commander-in-chief of its defence forces. He calls elections to the National Assembly and performs other duties defined by the Constitution. Borut Pahor was re-elected as President of the Republic of Slovenia for a second term in November 2017.

Slovene Parliament

The bicameral Slovene Parliament is composed of the National Assembly and the National Council. The parliament is characterised by an asymmetric duality, as the Constitution does not accord equal powers to both chambers.

The National Assembly, the highest legislative authority in Slovenia, is composed of 90 deputies. The National Assembly exercises legislative, voting and monitoring functions. It enacts national programmes, laws, constitutional amendments and resolutions, elects the Prime Minister and other ministers, and selects judges for the Constitutional Court, the Governor of the Bank of Slovenia, the Ombudsman and other key state officials. The National Assembly enacts its monitoring function through committees and commissions for special tasks.

The National Council is a mainly advisory body composed of representatives of social, economic, professional and local interests. Its 40 members are elected indirectly for a five-year term. Among its best-known powers is the authority of the 'postponing veto', ie it can demand that the Parliament re-discusses a certain piece of legislation. Following such a veto, the Parliament has to pass the law with an absolute majority.

Government

The Government of the Republic of Slovenia is a body of executive power and the highest body of the state administration, independent within the framework of its jurisdiction, and responsible to the National Assembly. The Government proposes laws to be adopted by the National Assembly, the state budget, national programmes and other acts through which the fundamental and long-term political directions for individual areas within the state’s competence are determined. It functions as a cabinet led by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is responsible for ensuring the unity of the political and administrative direction of the Government and co-ordinates the work of the ministers. He also proposes ministers, who are appointed and relieved of their duties by the National Assembly.

The state administration consists of the 14 ministries: Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of Public Administration, Ministry of Economic Development and Technology, Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities, Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, Ministry of Culture, Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning, Ministry of Infrastructure, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food, and Ministry of Defence. The government includes also the Government Office for Development and European Cohesion Policy and the Office of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia for Slovenians Abroad.

In January 2020, Slovenian Prime Minister Marjan Šarec resigned, ending the country's first minority government, a centre-left coalition. In March 2020, Janez Janša was elected as the 14th President of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia. The center-right Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS), formed a majority coalition with the center-left Party of Modern Center (SMC), the New Slovenia, and the pensioners' Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia (DeSUS).

Judiciary

Judicial powers in Slovenia are executed by judges, who are elected by the National Assembly. Judicial power in Slovenia is implemented by courts with general responsibilities and specialised courts that deal with matters relating to specific legal areas. The State Prosecutor is an independent state authority responsible for prosecuting cases brought against those suspected of committing criminal offences. The Constitutional Court decides on the conformity of laws with the Constitution; all laws and regulations must conform with the general principles of international law and with ratified international agreements. The Constitutional Court is composed of nine judges who are elected for a period of nine years.

Human Rights Ombudsman

The Ombudsman is responsible for the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms in relation to state and local self-government authorities and bearers of public authority. In January 2019 Peter Svetina was elected as the fifth Slovene Human Rights Ombudsman, for a period of six years, by deputies in the National Assembly upon the proposal of the President of the Republic of Slovenia. Since attaining EU membership, Slovenia has also had direct access to the European Ombudsman.

Local self-government

The basic units of local self-government are municipalities. The authorities of a municipality comprise a mayor, a municipal council (the highest decision-making body) and a supervisory committee. Mayors and members of the municipal council are elected by the residents in local elections every four years. The last local elections in Slovenia took place on 18 November 2018.

In 2018 there are 212 municipalities in Slovenia, 11 of which enjoy the status of urban municipality. The capital of Slovenia is Ljubljana, which is also the largest city; other urban municipalities are Maribor, Celje, Murska Sobota, Ptuj, Novo mesto, Velenje, Slovenj Gradec, Kranj, Nova Gorica and Koper-Capodistria.

National insignia

Slovenia’s coat of arms is in the shape of a shield with the outline of Mount Triglav in white, beneath which are two wavy blue lines representing the sea and the rivers, and above which are three gold six-pointed stars, arranged in the shape of an inverted triangle (a medieval symbol pertaining to the Celje counts, the last great local dynasty on Slovene medieval territory). As on the flag, the three national colours (white, blue and red) of Carniola - the central historic state of the territory of the Slovene people - are used.

The national anthem

The seventh stanza of Zdravljica [A Toast], a poem by France Prešeren (1800-1849) on the equal and peaceful co-existence of large and small nations in the world, is used as the Slovene national anthem. Zdravljica was written in 1844, and in it the poet declares his belief in a free-thinking political awareness, of Slovenes and all Slavs, promoting the idea of a Unified Slovenia, which the 1848 Revolution elevated into a national political programme. Zdravljica also became the call for a new internationalism. The music is written by Stanko Premrl and is taken from a choral composition of the same name. Extract from Stanza 7:

- God's blessing on all nations,

- Who long and work for that bright day,

- When o'er earth's habitations

- No war, no strife shall hold its sway;

- Who long to see

- That all men free

- No more shall foes, but neighbours be!

Population

The Statistical Office RS estimates that in 2015 Slovenia had a population of 2,063,077. According to the 2002 Cenzus, in addition to the majority community of 1,631,363 Slovenes (83.1 per cent of the total population), there are 2,258 Italians (0.11 per cent of the total population) and 6,243 Hungarians (0.32 per cent of the total population). The Italians and Hungarians are national minorities protected under the Constitution, each having a representative in the National Assembly. In ethnically mixed areas, bilingualism is guaranteed, nurseries and schools are provided for minority children, and minority languages are used by the local media. The status and special rights of Romany (Gypsy) communities living in Slovenia (3,246 people, 0.17 per cent) are determined by statute. Co-operation with and support for the Slovene minorities is carried out particularly in the fields of culture, sport and education; funds are also allocated for publishing and the media.

Other ethnic groups in Slovenia are: Serbs (38,964, 1.98 per cent), Croats (35,632, 1.81 per cent), Bosnians (21,542, 1.10 per cent), Albanians (6,186, 0.31 per cent), Macedonians (3,972, 0.20 per cent) and Montenegrins (2,667, 0.14 per cent).

After the dissolution of Yugoslavia, Slovenes living in the area of the former Yugoslavia became citizens of other countries overnight. There are several associations of Slovenes in Serbia and Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia and Croatia. Slovene minorities living in Italy, Austria and Hungary enjoy the right to use their own language and preserve their culture according to international agreements. In Italy, Slovenes live in the regions of Trieste and Gorizia and in the province of Udine. In this area the Republic of Slovenia is represented by the Consulate General of Slovenia in Trieste. The Slovene minority in the region has two main organisations: the Slovene Cultural and Economic Association and the Council of Slovene Organisations.

In Austria, the majority of Slovenes live in Carinthia, and are represented by the Consulate General of Slovenia in Klagenfurt/Celovec. Some Slovenes also live in Styria, where, however, they are not recognised as a minority. The main organisations of the Slovene community are: the National Council of Slovenes in Carinthia, the Union of Slovene Organisations, the Joint Co-ordination Committee of Carinthian Slovenes in Carinthia and the Cultural Association Article 7 in Styria. In Hungary, the Slovene national minority - around 3,000 people - resides mainly in the Porabje region, where Slovenes are organised within the Association of Slovenes, and the National Slovene Self-government. The Consulate General of Slovenia in Szentgotthárd operates in this area.

Slovene people emigrated in particular to both Americas (the USA, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Venezuela etc) and to Australia. These immigrants and their descendants find co-operation with the Republic of Slovenia in the areas of culture and education to be of particular importance. Much attention is also devoted to maintaining contacts with their country of origin and to strengthening Slovene identity among younger generations. At the present time between 250,000 and 400,000 Slovenes (depending on whether second and subsequent generations are counted) live outside the country, in other continents and in the countries of the EU.

In July 2006 two consultative bodies - the Council for Slovenes Abroad and the Council for Slovenes in Neighbouring Countries - were established as part of the recently-passed act on Slovenes abroad. The Council for Slovenes Abroad is comprised of 19 members - of which six represent state institutions and civil society organisations from Slovenia and 13 represent Slovenes abroad - led by a president and a vice-president. While the Prime Minister acts as the Council's president, the responsibilities of the vice-president are carried out by the incumbent Head of the Office for Slovenes Abroad. The make up of the Council for Slovenes in Neighbouring Countries is identical, apart from the division of its members with five representatives coming from state institutions and civil society organisations in Slovenia and five drawn from the ranks of Slovenes in neighbouring countries.

Almost 417,000 residents of Slovenia (every fifth) are first, second or third generation immigrants. More than half of immigrants are first generation immigrants, i.e. people whose first residence was outside Slovenia (mostly in countries on the territory of former Yugoslavia). (Stat.si Dec 2012)

Language

The official language of Slovenia is Slovenian, a South Slavic language spoken by only two million people. In nationally-mixed regions Italian and Hungarian are also spoken. The use of foreign languages in communication, including English, German, Italian, French and Spanish, is widespread throughout the country, while the Croat and Serb languages are easily understood.

The Slovenian language has played an important role throughout Slovene history. In spite of various influences, in particular Germanic, it has preserved its unique features. The most notable is the use of dual form, the grammatical number used for two people or things in all the inflected parts of speech, which is nowadays a very rare phenomenon in linguistics. Due to the varied relief of the territory and the various influences coming from neighbouring non-Slavic countries, many dialects developed alongside the standard language. According to some classifications, there are 36 separate dialects in Slovenia. Slovenian is now taught at more than 40 university departments in various European countries.

Foreigners have been increasingly interested in learning Slovenian, rising from 200-300 students each year at the end of the 1980s to 2,000-3,000 per annum in 2003 (figures from Slovenian language courses organised by the Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana). According to the latest Eurobarometer survey, released in Brussels in 2006, a total of 71 per cent of Slovenes speak at least one foreign language. Languages of neighbouring countries are the most favoured by the Slovenes (61 per cent), followed by English, which is spoken by 56 per cent of the Slovenes surveyed. This is considerably higher than the European average, which is 50 per cent.

In the context of events in celebration of the European Day of Languages (26 September), the Ministry of Culture, the Government Office for European Affairs (GOEA), the Information Office of the European Parliament and the Representation of the European Commission published a booklet entitled On Slovene in cooperation with staff of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Ljubljana. This short Slovenian-English publication is intended for a wider public and presents the role, status, historical development, geographical usage, and grammatical structure of the Slovenian language. The last part addresses the challenges facing Slovenian in the 21st century, particularly with regard to the multilingual environment of the European Union. In addition, the use of Slovenian as one of the EU official languages within the European Parliament has been described in more detail. An excerpt from the Resolution on the 2007-2011 National Programme for Language Policy outlines the vision of development in the light of institutional care for the Slovenian language to be provided by the state.

Religion

Along with the guaranteed right of the preservation of national identity, the people of Slovenia have a right to their own religious beliefs. According to the 2002 census the largest section of the population (57,8 per cent) are Roman Catholics. 0,8 of the population declared that they belong to the Protestant Church (it has its roots in the Reformation, and is most widely spread in the eastern part of Slovenia), 2,3 per cent to the Orthodox Church and 2,4 per cent to Islam (census 2002). Around 38 other religious communities, spiritual groups, societies and associations are also registered in Slovenia.

Society

At the end of March 2007 there were 2,013,597 people living in Slovenia. Approximately 50 per cent of the people reside in urban areas and 30 per cent in towns with more than 10,000 inhabitants, whilst the rest live in nearly 6,000 smaller towns and villages. The municipalities of Ljubljana (265,881, 2002 Census), Maribor (110,668), Kranj (51,225), Celje (48,081) and Koper-Capodistria (47,539) are Slovenia’s five largest urban settlements.

The population density currently stands at 98.7 inhabitants per square kilometre, a figure much lower than in the majority of other European states. People have mainly settled the river valleys and transport routes, where long ago Slovene towns began to emerge, whilst the mountainous and forested areas remain unpopulated.

Slovenia’s population is slowly declining and the country has the lowest birth rate both in Europe and the world, although the figure of 18,932 live births in 2006 was the highest in the past decade. The average number of people per household is decreasing (in the last census in 2002 it was only 2.8) and the number of marriages is also falling, whilst the average age of mothers having their first child is increasing - in 2006 it was 28 years. In the 2002 Census almost a half of families with children (49 per cent) had only one child. In 2004 the life expectancy for men was 73.48 years and 81.08 for women, which is approximately three years longer than in the mid 1990s. People living in Slovenia have good education and employment opportunities, and are well educated by all the usual indicators.

Education

The Slovene school system has seen a number of changes in recent years, aiming to raise awareness of educational rights and thereby achieve a higher educational level. The nine-year programme, for which no pre-school education is compulsory, is divided into three periods of three years, beginning when children are six years old. Parents can choose between the elementary education programmes provided by public nine-year elementary schools, private elementary schools or home-schooling. In practice almost all of children attend public nine-year single structure elementary schools within the school district of their residence.

At the beginning of the 2014/15 school year 170,700 children were enrolled in basic education. Compulsory basic education is carried out by 787 elementary schools and their branches and by 56 elementary schools with special curriculum, including their units. (Source: Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia)

After completing elementary school, nearly all children (more than 98 per cent) go on to secondary education, either vocational, technical or general secondary programmes (gimnazija). The latter prepare students for further studies and are divided into two groups: 'general' (classical gimnazija) and professionally oriented (technical, economic or art gimnazija) leading to external matriculation examinations. Children of foreign residents are also appropriately provided for in Slovenia and can receive education at all levels. 84 per cent of secondary school graduates go on to tertiary education.

In the academic year 2014/15, 83,700 students are enrolled in tertiary education. The educational system in Slovenia is almost fully financed by the state budget. The share of the gross domestic product allocated to education increased from 4.76 per cent in 1992 to 6 per cent in 1998, in 2013 it is 1,971 million Eur or 5.5 per cent of GDP. In 2013 EUR 2,194 million or 6.1% of GDP was spent for educational institutions. 86% of expenditure for educational institutions was public expenditure, slightly less than 13% was private expenditure and only 1% was funds from international sources.

The educational profile of Slovenia's population is improving. According to the 1991 census there is 99.6 per cent literacy in Slovenia. Among people aged 25 to 64, 12 per cent have attended education and training in 2014, whilst on average Slovenes have 9.6 years of formal education. The best educated are those employed in the area of education and public administration. Lifelong learning is also increasing.

The university system

Higher education in Slovenia began with the arrival of the Jesuits in Ljubljana in the first half of the 17th century. Subsequently, in what was to be the first of many initiatives aimed at establishing a university in Ljubljana, an association of important cultural workers, theologians, doctors and lawyers known as Academia Operosorum attempted unsuccessfully to establish a complete theological and philosophical faculty in the city. Some two centuries later national consciousness and a longstanding desire for the affirmation of the Slovene language were fulfilled with the establishment of the University of Ljubljana with five Faculties - Law, Arts, Technical, Theology and Medicine.

Today, Slovenia has four universities: the University of Ljubljana, the University of Maribor, the University of Primorska and the University of Nova Gorica. The University of Ljubljana now encompasses 23 faculties, three art academies and three associated members (National University Library, University of Ljubljana Central Technical Library, University of Ljubljana Innovation-Development Institute). The University of Maribor, which was founded in 1975, consists of 15 faculties and colleges, the University of Primorska, which was founded in 2015 has seven faculties and two institutes. The fourth Slovene university, the University of Nova Gorica, established in 2006, encompasses five faculties and colleges.

No tuition is charged for state-approved undergraduate study programmes offered as a public service (full-time studies). Scholarships and grants for part-time studies are offered by ministries, public and private funds and employers. Additionally there are seven private single higher education institutions. Vocational colleges were introduced by the Vocational and Technical Education Act of 1996 and are institutionally separate from higher education. In the academic year 2006 there were 48 vocational colleges, of which more than half were private, offering 22 study programmes. Business studies, secretarial and accountancy programmes proved the most popular with students.

In the academic year 2014 the number of students at the University of Ljubljana is 42,922 (the number of foreign students being 1,865). In the academic year 2014/2015, a total of 16.680 were enrolled at University of Maribor.

In the 2009/10 academic year, the majority of Slovene students went on exchange to Spain, Germany and Portugal. On the other hand, Slovene tertiary educational institutions hosted mostly Polish, Spanish, Czech and French students.

Slovenia and the Central European Exchange Programme for University Studies (CEEPUS)

In 2005 Slovenia assumed the presidency of the Central European Exchange Programme for University Studies (CEEPUS), a network of universities and university colleges that want to improve mobility in Central Europe by exchanging students and professors for at least one semester. Each country must provide funds only for months of study, but the money stays in the country and is intended only for foreign students and lecturers who come to Slovenia. Next to the scholarship the students are covered accommodation, basic medical insurance for the whole stay in Slovenia if applicable, food and public transport subsidy. Teaching staff amount is intent to cover all costs, including accommodation. A National CEEPUS Office is the CMEPIUS - Centre of the Republic of Slovenia for Mobility and European Educational and Training Programmes.

The priority of Slovenia's presidency was CEEPUS II with an emphasis on joint degrees. These enable students to obtain degrees from two universities co-operating in the network. At the 11th CEEPUS ministerial, an award was given out for the best network. It went to a network of 15 universities called Language and Literature in the Context of Central Europe, which included the Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana.

Sources

- National Statistics Office website

- Facts about Slovenia, Government Communication Office, Ljubljana (last update June 2011, PDF)

- Discover Slovenia, Cankarjeva založba, Ljubljana (1996)

- Encyclopedia Slovenia

History

- Milko Kos, Zgodovina Slovencev: od naselitve do petnajstega stoletja, Ljubljana: Slovenska matica, 1955 (‘History of Slovenes – from the settlement to the 15th century’)

- Bogo Grafenauer, Zgodovina slovenskega naroda (1-5), Ljubljana: Državna založba Slovenije, 1954-74 (‘The History of Slovene Nation’ in 5 books)

- Bogo Grafenauer, Od naselitve do konca 18, stoletja, Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba, 1979 (‘From the settlement to the end of the 18th century’)

- Metod Mikuž, Oris zgodovine Slovencev v stari Jugoslaviji, 1917-1941, Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1965 (‘An outline of the history of Slovenes in old Yugoslavia’)

- Metod Mikuž: Pregled zgodovine narodnoosvobodilne borbe v Sloveniji (1-5), Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba, 1960-1973 (‘An overview of the history of the fight for liberation in Slovenia’)

- Zgodovina Slovencev, Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba, 1979 ('History of Slovenes')

Slovenska novejša zgodovina, 1948-1992. Ljubljana: INZ, Mladinska knjiga, 2005 ('Slovene contemporary history')

- Peter Vodopivec, Od Pohlinove slovenice do samostojne države - Slovenska zgodovina od konca 18, stoletja do konca 20, stoletja. Ljubljana: Modrijan, 2006 ('From Pohlin's Grammar up to an independent state - history of Slovenia from the end of 18th century through to the end of 20th century')

- Peter Štih, Vasko Simoniti, Peter Vodopivec, Slovenska zgodovina: družba - politika - kultura, Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2008 ('Slovenian History: Society - Politics - Culture')

Sources in English

- The Land Inbetween: A History of Slovenia

With contributions by Oto Luthar, Igor Grdina, Marjeta Sašel Kos, Petra Svoljšak, Peter Kos, Dušan Kos, Peter Štih, Alja Brglez and Martin Pogačar.

Contents: From Prehistory to the End of the Ancient World - The Early Middle Ages - Feudalism - The Early Modern Period - Modernization and National Emancipation - From the Habsburg Monarchy to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia - From a Socialist Republic to an Independent State.

The first comprehensive history of Slovenes in English was published in autumn 2008 by Peter Lang Publishing Group. The book is an accurate scientific work giving special attention to cultural history, the result of years of work by nine Slovenian historians, archaeologists and anthropologists. On over 500 pages the book presents Slovenia from prehistory to its entry into the EU in 2004.